Birds, bees and boobs: the modern day sex talk we need to have

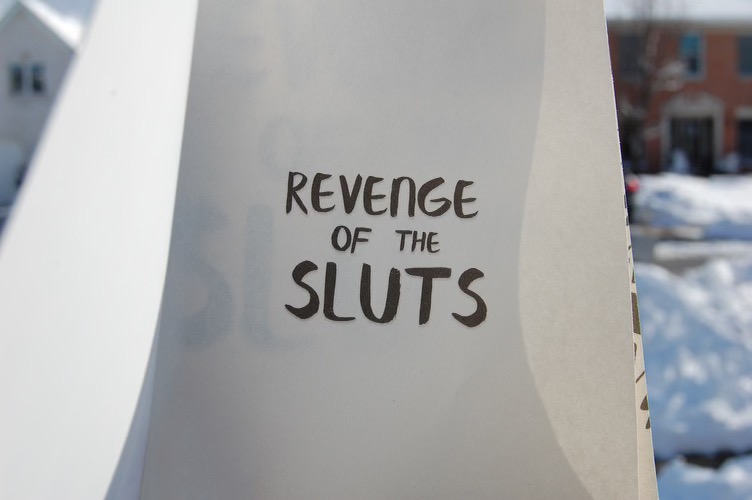

Natalie Walton’s debut novel “Revenge of the Sluts” releases tomorrow, Feb. 2, 2021.

Trigger warning: This article contains mentions of sexual violence, harassment, nonconsensual (revenge) pornography, cyberbullying and death.

“It had all started with a pair of boobs.”

Maybe it shouldn’t have started like that. Maybe it shouldn’t have started at all. Maybe the girls shouldn’t have taken and shared the photos in the first place. Maybe the recipients shouldn’t have sent the photos around. Maybe it’s the girls’ faults. Maybe they’re the victims here.

Among all these maybes, only one thing seems certain: intimate photographs of seven students were released in mass email to all of St. Joseph’s High School. The so-called “Nudegate” has caused the girls involved to be dubbed “sluts” for their actions, but they won’t let what people say get to them. Natalie Walton’s “sluts” are here to pursue their justice in Walton’s remarkable debut novel “Revenge of the Sluts.”

The girls are not alone in their attempt; the staff of St. Joseph’s newspaper, Warrior Weekly, is right beside them in reporting the events unfolding and attempting to discover who the mysterious sender “Eros” is. Eden Jeong, executive editor of staff, is in charge of attaining student perspective on the incident as well as getting statements from the girls involved to share with the school. That is, if they’re willing to speak.

Subsequent interviews and research leads to Eden discovering that not only are members of the student body negatively perceiving the girls, but they also have an overbearing enemy in the school’s administration. Instead of making an effort to support the girls, it seems as if the school is more focused on protecting their reputation by ensuring that media outlets, including Warrior Weekly, do not gain more insight on Nudegate.

The curiosity, frustration and persistence of Eden’s character during this circumstance are all an accurate depiction of how most student journalists feel when writing their pieces. Above all, journalists value the truth and sharing factual information with people, not censoring or providing editorialized accounts of events. Warrior Weekly isn’t able to do this, and I doubt many other publications would be able to either.

At a student level, limitations on student publication generally exist in the form of censorship. While the First Amendment protects some rights of student journalists, The Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier United States Supreme Court decision of 1998 allows administrators to censor school-sponsored publications if they provide a reasonable rationale.

According to the Student Press Law Center, “when something is primarily a curricular publication, student speech can be censored for a legitimate educational reason. When something is primarily a vehicle for student expression, it can only be censored when the content is illegal or creates a substantial risk of a material disruption of the educational process (that is, some physical event that stops school from happening normally).”

Professional journalists aren’t subject to those same restrictions, which can be both good and bad. In their 2019 SuperBowl advertisement, The Washington Post reflected upon their slogan “Democracy Dies in Darkness” to show the risks professional journalists take each day. Professionals are forcibly silenced through threats, murder, sexual assault and other means of harassment. While they’re able to seek out and expose the truth, they risk their own lives to do it.

Warrior Weekly’s struggles with censorship may seem trivial in the broader context, but in all honesty, they’re still royally messed up. I don’t know if it’s the journalist in me speaking or the fact that I’m a human, but it feels so weird to me to know that schools are more concerned about their reputations than the well-being and safety of the students that fund them.

If this happened to me, would I be silenced? If I were assigned to write this article, would my work be censored? Would I be okay with everything that I read about actually happening to me or someone else in real life?

Because the unfortunate truth is that the social issues that Walton discusses aren’t just fictional. Nonconsensual pornography (NCP) occurs and has been defined by the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative (CCRI) as “the distribution of sexually graphic images of individuals without their consent.” Research collected by the CCRI has shown that victims of NCP have 23% higher scores of physical burden and 7% lower mental health scores than non-victims.

Those results are from 2017—from the first national study for nonconsensual pornography victimization. This isn’t a conversation we should have started only three or four years ago; we should have had this discussion when apps with disappearing photos and messages like Snapchat launched in 2011.

With the rise of social media over the past decade and with a world that’s existing digitally during the pandemic, I think it’s more important than ever for people to open their dialogue regarding sending and receiving intimate photographs, slut-shaming, victim-blaming, double standards for being sexually active and censorship in our modern age.

Instead of starting with another “pair of boobs,” I hope Walton’s “Revenge of the Sluts” starts the conversation we’ve been avoiding for years.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Neuqua Valley High School. Your contribution will allow us to print our next newspaper edition as well as help us purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.