Signs on the sidewalk: a look at socialism, freedom of speech and other current issues

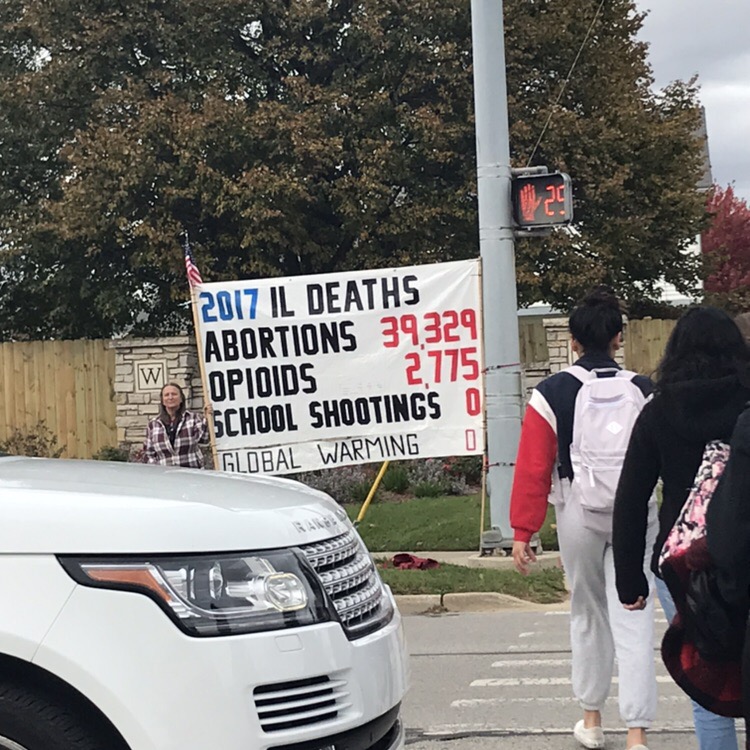

Sliva stands across from the school with one of her signs as students leave for the day. Photo by Bhoomi Sharma.

January 22, 2020

Last spring, Renata Sliva, a Naperville resident, began standing across from Neuqua Valley High School with large banners sporting a variety of messages addressing topics such as Marxism and abortion. About once a week, she sets up her sign and stands on the sidewalk at the corner of Skylane Drive and 95th Street after school gets out and Neuqua students begin walking home.

Not pictured are two of Sliva’s other signs. One says “socialism = lies + death.” The other says “reject Marxist lies; embrace civilisation,” and has the intertwined symbols for men and women.

Sliva says…

Sliva says her main goal is to raise awareness about socialism and the dangers she believes are associated with it because she feels students are not well educated about it. Sliva grew up in socialist Czechoslovakia, so she feels a personal connection to the subject.

Sliva describes socialism as, “a way… to distribute justly… what is produced.” Merriam Webster defines socialism as “any of various economic and political theories advocating collective or governmental ownership and administration of the means of production and distribution of goods.” Sliva made it clear that she believes socialism is inherently tied to authoritarian or dictatorial rule, at least in terms of practical implementation, saying, “[socialists] promise people a lot of things, and once they are in power, they can force … dictatorship, basically.”

She also feels socialism has links to other moral or ethical issues within society, such as the legal right to obtain an abortion and the legalization of gay marriage nationwide. She says that these issues are used “to punish opposition.” In her view, an essential part of Marxism — a specific version of socialism — is the opposition of religion, and especially in America, Christianity. She said that it could be, “any other issue,” but these ones in particular are important because they, in her view, go against Christian morality.

Sliva credits Christianity with a number of important historical events — including the founding of the United States and the end of slavery in the country. She draws a connection between the religion and morality more generally. She also describes “the traditional family structure,” as the way, “people grow up… with truth and values.” This is important in terms of her concerns with socialism, she explains, because “[socialists] don’t need moral people.” She believes that the progression of socialism would benefit from a moral downturn — at least according to the standards of traditional or conservative Christianity — within society. She says, “they don’t want to keep the family together…if people are promiscuous…they are not moral.” According to Sliva, this contributes to people being easier for socialists to lead and control.

As evidence for her claims, Sliva cites her own experiences in growing up in Czechoslovakia. She recounts that “[they] basically had two churches — one underground and one … official,” and explained that restricting religion was one way the government controlled the population. She claims that the “[promotion of] easy abortion and easy marriage… no restrictions,” mirrors what happened in communist and socialist countries, as she points out that many of them legalized abortion. She thinks that, fundamentally, socialists “don’t value life.” She also described her own experience going through the school system there, and said that what she sees in the United States now reminds her of it.

One of Sliva’s main concerns is that “[socialists] lie.” She feels Neuqua students — and students at the other high schools she visits — “are not being taught the history… American or about socialism.” Her concerns lie both with the curriculum itself and the ways the school tries to offer enrichment to students. She believes the way the school teaches the history, including that surrounding socialism and Christianity, is incomplete.

She believes the curriculum is liberally biased, which she disapproves of. She feels the schools do not present an honest picture of the negative impacts she feels socialism had and the positive impacts she believes Christianity had. She also takes issue with the bias that she perceives in the outside speakers the school invites to share with students, feeling that conservative speakers are not given a fair chance.

She says she does not wish to prevent liberal speakers from presenting, but she believes that conservative speakers should have equal representation and does not feel that is happening at schools like Neuqua.

Historians say…

In the last century or so, socialism and communism have played influential roles on the world stage. In the early 1900’s, the Russian Revolution brought about the creation of the Soviet Union. The second world war was followed by the Cold War — often seen as a competition between communism and capitalism.

One of the first major influencers and proponents of communist ideas was Karl Marx. Because of “the Communist Manifesto,” which Marx co authored with Frederick Engles, these original ideals are often called Marxism.

Throughout history, communism has had multiple interpretations and forms as different people have tried to implement their own vision of it. These forms include Leninism, Trotskyism, Stalinism and Maoism. Though communism and socialism are different things, there have been similarities between the attempts to implement them.

Many authoritarian communist and socialist countries including the Soviet Union did target religion in an attempt to gain control of a population. Religion has been a way of uniting and influencing people for most of history. The tactic of religious assimilation aided the conquest of the Roman Empire. The Roman Catholic Church was one of the most powerful political bodies in Europe during the Middle Ages. The idea of total religious freedom is in itself a relatively modern one.

The role of religion and religiously based moral beliefs in legal policy is still a debated topic in the United States and a number of other countries. The United States was the first country to include the concept of “separation of church and state,” in its founding principles. It was also one of the first modern Western countries without a state church.

In terms of morality — at least as far as there is a consensus on what that means — Christianity has a checkered history. One of Sliva’s examples is the end of slavery in the United States. As Sliva pointed out, there were Christian abolitionists and other Unionists who were motivated by passages in the Bible to seek the end of or limitation of slavery. For many years up to and including the Civil War, however, passages in the Bible were also used by Christians to justify slavery and suggest that slaves had an obligation to be obedient. There were arguments for both sides made from the stance of Christian morality.

The Civil War was not the only time groups of Christians held contradicting opinions on important issues of the time. Christianity is not a united movement — it’s an umbrella term for a group of denominations. Christians, like most groups and religions, are responsible for both some positive and some negative happenings in history and are completely uninvolved in others.

Currently, different Christian denominations, churches and individuals are divided on a number of moral issues as well, including the rights to gay marriage and abortion. Silva’s views on Christian beliefs seem to align more with conservative Christianity. In terms of the religion, “conservative” does not denote a political stance — though the two do sometimes go together — but rather describes a tendency towards a more literal interpretation of the Bible and religious doctrine. One the other side of the spectrum is progressive Christianity, which believes in a less black and white approach to interpreting the Bible.

Neuqua teachers say…

Paul Whisler, an AP World History teacher at Neuqua Valley, addressed Sliva’s concerns about the history curriculum at schools. He explains that “there’s a lot of moving parts,” when it comes to creating curriculum for history classes. Certain classes, such as AP classes, have outside standards they have to align with in order to be part of those programs. Many classes are created and workshopped by curricular teams of teachers within the district.

He says the process is “a lot of negotiation,” as teachers discuss what content, skills, and standards should be included in a class. He says it can be “hard” for history classes like AP World History, which cover long time periods and wide ranges of topics, as there is no way to teach everything. As a teacher, Whisler says he works to ensure his students understand both the material they’ll be expected to know for exams and any other important parts of world history in the time periods they cover. One challenge he points out is, “pacing — what to do when you get behind, how do you catch up,” so that students will go through all the material of the course, and have enough time with different topics to understand them.

He describes curricular and lesson planning as a “balancing act that all teachers are trying to play.”

As far as bias in the curriculum, Whisler says that “everybody has bias,” but he thinks the teachers in district 204 are “professional enough that [they] understand that.” He doesn’t think any of the teachers would intentionally choose to present their biases or viewpoints to students. According to his description, avoiding bias and ensuring students can learn the information and explore it for themselves through multiple perspectives is a point of professional pride for teachers.

He does note that history is a complicated subject, explaining that there are classes that focus on much smaller time periods or regions and are able to go more in depth, typically at the collegiate level. Whisler says the teachers in district 204 work to make sure students have a good foundation of historical knowledge and skills.

Whisler also believes that the school does not promote bias when inviting outside speakers to speak with students. The school has hosted people of a variety of political stances and beliefs. Whisler says that one of the main factors that play into finding outside speakers is opportunity — who is available and willing? He says that teachers will work to make sure that speakers are qualified in the area they’re coming to speak about and gave the example of a Second-Amendment lawyer who spoke to students. Whisler explained that the lawyer was experienced and knowledgeable in his field. The decision to bring him in wasn’t because of or prohibited by the lawyer’s stance on the Second Amendment. As a teacher, Whisler feels that bringing outside speakers is a good way to add to a student’s education.

Christina Jakubas, an English teacher at Neuqua and a staff sponsor for the Women’s Empowerment Club and Gay-Straight Alliance at the school, works with clubs seeking to provide students with a voice when it comes to issues that may impact them personally or that they are invested in.

She explains that issues like the rights to abortion and marriage are complex issues. She says that the pro-choice movement has “long been wrapped up in women’s rights.” Jakubas notes that the first options for birth control became available in 1916, and she believes this history plays into current mindsets around the movement as well, saying it’s about “what individuals are in control of as far as making decisions for their own bodies.”

She says that the movement for equality for members of the LGBTQ+ community can be traced back to “as early as people have been identifying,” but points out the events at Stonewall in 1969 as “a landmark,” for the movement in America. She says that it has been a long process, and that its influence is often extremely personal. “If you’re a member of the LGBTQ+ community, this has been your life — a constant negotiation of rights and identifying who you are within a greater culture that has overwhelming not been accepting.”

For both issues, Jakubas says that she believes it’s important for people to understand where they themselves are coming from and to understand that everyone has their own experiences. She says that, “whether it’s coming from a religious or political base, or their own experiences, we have to be mindful that everyone has their own experiences.” She does also believe it is important to consider the people affected by any laws passed or decisions made. She believes that ultimately, both issues are based in human rights.

The First Amendment says…

The First Amendment of the United States Constitution reads, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” It protects a number of freedoms, including free speech.

Sliva’s form of activism, which takes place on public property, is protected as a peaceful exercise of free speech under the First Amendment. The same type of demonstration — bringing a sign and talking to students — would not be allowed, however, on school property out of concern for student safety. Those wishing to engage with students this way are required to stay on areas like public sidewalks.

Some protests or demonstrations require permits, however this is usually determined by the size of the demonstration and the impacts it might have on traffic flow and other logistical issues. Standing on a public sidewalk, for instance, does not require a permit, while forming a march usually would.

Sliva’s own children attended school in district 204 and she feels motivated by that. She also says she “was not personally in [a] … socialist prison, but [she] knows people who were,” and she feels motivated by those experiences. She explains that she feels it her “duty to warn people.” She says she chose to use signs as a method of raising awareness because she feels there is not an accurate representation of her beliefs from news and media sources and feels limited in her other options.

Students say…

The Neuqua students who walk by Sliva’s signs after school expressed a variety of opinions on the matter. Many said that they didn’t really notice it or think much of it. They said it didn’t affect their experience getting home. One student said he “[finds] it funny,” but otherwise doesn’t pay much attention to it.

A number expressed frustrations or concerns. One student remarked that she, “[doesn’t] like it,” and thinks Sliva should, “go somewhere else.” Other students echoed the sentiment, saying they didn’t approve of Sliva’s actions, either due to the message or how close it was to the school.

The majority of students who voiced opinions, however, said they were confused. “I don’t really know what she’s trying to do,” one said. These students said they had noticed the signs but felt they didn’t understand what Sliva was trying to say with them. A few said they’d stopped to ask, but most did not.

The administration says…

In previous years, Sliva has exercised her right to speech in a number of other ways. She has spoken to the school board about her concerns, and also ran for a position on the board. Karen Lawson, the English Department Chair at Neuqua, explains that Sliva ran a website called watchdog 204, wherein she detailed anything within curricular English books that she believed might concerns parents. She spoke to the Neuqua staff about curriculum for English and other courses. Lawson says that all parents are welcome to request information about curriculum for their children’s classes, as the school wants parents to be aware of what their students are learning. She described an admiration for Sliva’s involvement and her exercise of her freedom of speech, even if Lawson didn’t always agree with points she raised.

One thing that set Sliva apart from other parents, however, was her interest in the curriculum outside of what her own children were learning. Neuqua, like other public schools, allows parents to make decisions about what is and isn’t appropriate for their children to read or watch in school. If a parent has a concern, they can ask for an alternative assignment for their child that will teach and test the same skills in a different way. Sliva, however, expressed issues with some of the books being taught to students at all.

Robert McBride, former principal of Neuqua Valley also interacted with Sliva while her children went to Neuqua.He was also principal when she first began standing across from the school. He says that her children attended Neuqua first, but after boundary shifts went to Waubonsie. He says, “her interest, though, in the curriculum at Neuqua — as well as the other two schools — remained the same.” He says that in his experience with her, Sliva used “the normal channels to communicate concerns about the curriculum.” McBride explains that meant, “request[ing] from teachers … department chairs… or administrators information about books being read or topics studied. Also she would request information about how the decision was made to use that particular curriculum.” As Lawson said, all parents can request information about the curriculum for their children.

McBride says Sliva did request information on classes her children were not enrolled in, which was more unusual. In terms of expressing any desires for change, Sliva typically went to the school board about the concerns she had. The school board, the body of representatives elected by the people in the district, is involved in approving curriculum. McBride says Sliva typically presented her thoughts during the “public comment,” part of the meetings.

McBride says that the primary issues Sliva raised concerns about as far as he knew involved “sexuality… politics… and violence.” He says that Sliva was respectful when requesting information and dealing with the staff in his time.

Though Sliva has not mentioned the movement, McBride notes that her choice to stand across from the schools coincided with an effort from parents around the Chicagoland area to do similar demonstrations.

In conclusion…

Sliva says she intends to continue standing across from Neuqua so that Neuqua students will be exposed to her beliefs. The Neuqua community has had a mixed reaction to her efforts so far. Sliva and members of the Neuqua staff like Jakubas did share one perspective, however, — the desire for students to look into issues for themselves and form their own opinions.

Additional information about the article —

Due to the complexity of the issues and Sliva’s beliefs, the Echo is — with her permission — including a full recording and transcript of her main interview for this story. All quotes from Renata Sliva are from the included interview.

Student interviews were conducted at the intersection of 95th and Skylane, opposite where Sliva stands as students were leaving the building, and were conducted over the course of about three weeks with as many students as wanted to talk about it during that period.

Renata Sliva • Jan 27, 2020 at 9:18 am

Thank you, Abby, for the article and I really appreciate the time you put in it.

James Neighbors • Jan 25, 2020 at 8:32 pm

I have to say this is the first objective journalism I have seen in decades.

You presented both sides, the facts, the background, opposing opinions, without making an opinion of your own.

THANK YOU.

This is the first article I’ve read on The Echo, but I hope this is an indication of the journalist integrity of the entire publication.

Journalists aren’t supposed to take sides, and you did not. THANK YOU AGAIN!