What is the For the People Act?

Members of Congress stand in the US Capitol speaking to the press about the For the People Act.

March 9, 2021

Democrats, who took control of both chambers of Congress in late 2020, are working to pass one of their first big pieces of legislation: a voting rights bill called the For the People Act. The bill, which if passed into law will greatly expand the number of eligible voters, passed the House on Wednesday, March 3 with 220 voting yes and 110 voting no. Next, the bill will be put up for a vote in the Senate. The Democrats do hold an advantage in the Senate, according to APM Research Lab, as 48 Democrats hold Senate seats, and two Independents, Bernie Sanders and Angus King, caucus with the Democrats (meaning they meet with them, and are more likely to vote for Democratic supported bills). This leaves 50 Senators of each party in the Senate, but Democratic Vice President Kamala Harris casts the tie-breaking vote in such a case, and the Biden administration signaled its support for the bill in an official statement a day after the House voted to pass the bill to the Senate.

The For the People Act is a wide ranging bill that aims to secure the right to vote for more Americans, make voting easier for those eligible to and make the electoral process more fair overall. The bill plans to re-enfranchise all citizens who have been convicted of one or more felonies and fully completed their sentence. Across the country, 19 states have somehow restricted felons’ rights to vote after they have completed their prison sentence, according to a Jan. 8, 2021 report from the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL). Additionally, according to the NCSL, 11 states in some way restrict felons’ right to vote after completing their sentences if they have committed certain crimes. Given these restrictions, according to a 2020 project from The Sentencing Project, 5.2 million Americans cannot vote due to past felony convictions. A caveat to the bill’s goal of total re-enfranchisement for felons is that felons cannot vote while they serve their prison sentences; currently only the District of Columbia, Maine and Vermont allow felons to keep their voting rights while incarcerated. The bill’s language speaks only of restoring former felons’ right to vote, so it seems that those three principalities’ incarcerated felons will keep the right to vote under the bill.

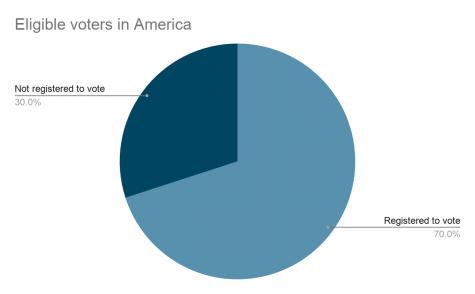

The Act’s aims of enfranchisement are not limited to out-of-jail felons, with the bill detailing an automatic voter registration system for all eligible voters, with an option to opt out. According

to the US Census Bureau’s data from the 2018 midterm elections, about 153 million people were registered to vote. According to an estimate for July 2021 made by the US Census Bureau this past December, there will be about 256.6 million residents of the United States who are of voting age (18 and above). The US Census Bureau estimate does not account for whether a resident is a citizen, but according to a 2019 report from the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), 93.3% of those living in the US are citizens (this includes all residents, not just voting age residents). Given these numbers, it can be estimated that there are roughly 220.7 million eligible voters in America. Based on this data, there are roughly 67.7 million people eligible to vote who are not currently registered that an automatic voting registration system would help.

Along with enfranchisement, the bill would implement, in its own words, “anti-corruption measures for the purpose of fortifying our democracy,” including expanded transparency for donations received by political campaigns and a reformed districting system. The financial aspect of the reform the bill hopes to achieve would require organizations that pool donations they receive and give these pooled funds to politicians to disclose who initially donated the money that ends up in politicians hands this way. This would apply to super PACs (very large political action committees) and dark money (money donated to politicians by nonprofits incorporated under section 105c). The bill would also require Twitter and Facebook to say when a political ad is paid for, additionally requiring the sites to list who paid for it and how much they paid for it.

The redistricting changes the bill proposes are in response to the political practice of gerrymandering. Gerrymandering means that maps that determine congressional districts are drawn to unfairly favor one of the major parties (both Democrats and Republicans have partook in gerrymandering throughout its history) by choosing to deliberately include or exclude demographics which tend to vote one way. The process went to the Supreme Court in a 2016 case, but the justices declared it a “political issue.” The For the People Act’s political solution to this problem is to mandate each state employ independent commissions to redraw congressional district maps. These commissions would require “an equal number of Republican, Democratic, and unaffiliated members, with voting rules designed to ensure that no one party can dominate the redistricting process,” according to the Brennan Center for Justice.

The bill contains many more changes in its 800+ pages, but these are the main three prongs of the Act, and some of the most controversial as it awaits its fate in the Senate. While the Democrats do hold a slim controlling stake in the Senate, Senate Republicans may use a filibuster (a tactic that delays voting on a bill through a variety of means, such as very long speeches or emphasis on minute yet time consuming procedural requirements) as they have before used to prevent the passage of legislature proposed by Democrats. It is important to note that Senators from both parties have used the filibuster, and though Senate Democrats are campaigning for its abolishment, one of the staunchest supporters of keeping the tactic is Joe Manchin, a Democratic Senator. The movement to pass the For the People Act and to abolish the filibuster may go hand in hand, with the outcome of the latter determining the outcome of the former a likely possibility.